Let's talk about...

Racial disparities in pain assessment & treatment

Empirical evidence of racial biases in pain assessment and treatment is prevalent. To highlight the scope of the problem, here are a few statistics. Primary care providers are twice as likely to underestimate pain in Black patients compared to all other ethnicities combined (Staton et al., 2007). Black patients are seen as more likely to require scrutiny for potential drug abuse (Becker et al., 2011), even with evidence the scrutiny is unwarranted (Becker et al., 2008).

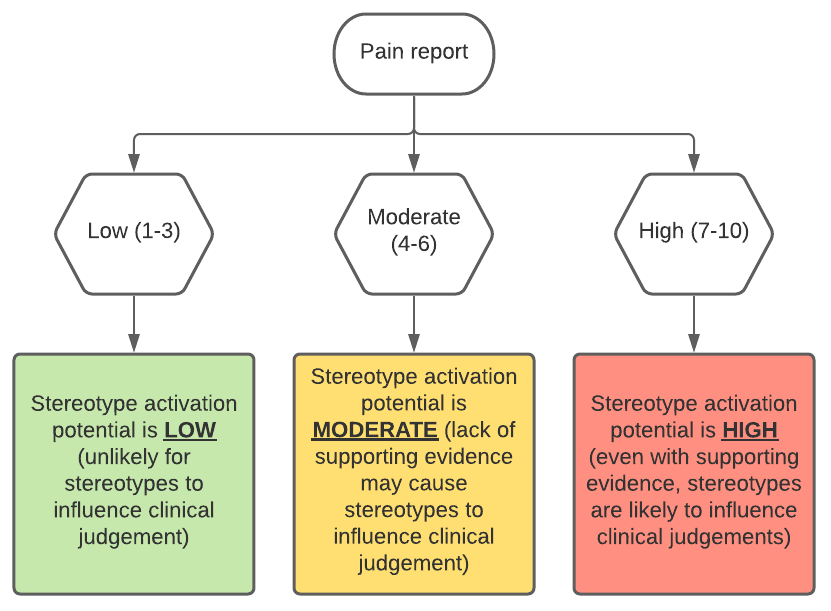

To understand the reasons behind racial disparities in pain assessment, we first need to understand the issues with using a subjective measure, such as a pain report. The difficulty with subjective measures in the context of healthcare is the lack of objective assessment leaves room for interpretation and makes the measurement susceptible to psychological influences, such as stereotypes.

Below is a diagram adapted from Tait and Chibnall (2014) providing a general overview of the way pain severity relates to the likelihood of stereotype activation in healthcare.

An additional issue with pain measurements is these reports can be biased. For example, self-reports are often challenging to understand when a patient’s primary language is not English, individuals with cognitive difficulties may find rating scales difficult to follow, and some researchers criticize self-reports as unidimensional attempts to assess a multidimensional experience (Tair and Chibnall, 2014).

However, the primary issue we will focus on here is stereotype activation. In contexts where there is subjectivity, there is an element of uncertainty, which can lead to stereotype activation. Stereotypes will advantage patients that fulfill positive stereotypes and disadvantaging patients who do not. This problem has been investigated outside healthcare contexts, as well. In two experiments, study participants viewed videotapes of patients in pain and found more aggressive treatment recommended for white patients (Drwecki et al., 2011; Kaseweter , Drwecki, and Prkachin, 2012).

In general, pain assessment is influenced by three primary components: (1) patient features, (2) situation (i.e. medical evidence), and (3) healthcare provider experience (Tair and Chibnall, 2014). To further elucidate cognitive mechanisms at work in pain assessment and treatment, there are two cognitive processes that require acknowledgement. The first is evidence-based (i.e. situation specific, conscious, logical, and effortful) and the second is intuitive (less situation bound, automatic, less effortful; Tair and Chibnall, 2014).

What Can Be Done?

Now that you have a better idea of the issue, how can we address some of these biases in our own patient interactions? First step is making sure you are aware of the issue (done!). Awareness allows you educate yourself on how you can best self-monitor your own biases. All humans have biases, our brain is designed to group concepts, ideas, and people together. This is a way our brain maintains efficiency; however, grouping can become harmful when it leads to generalized notions about specific group members (i.e. stereotypes). However, the good news is the brain has plasticity! Monitoring yourself is an active process, until your thought patterns change and then it becomes a passive one.

Active information processing means remaining mindful of your own cognitive processes while completing a task (Seamone, 2006). The “active” nature can be triggered by writing or stating aloud the way you arrived at your judgement. You can also implement checklists, which run through different bias-reducing techniques, such as perspective taking.

If you are interested in more structural changes that are patient-focused, there have been interventions applied within hospitals or across entire countries. For example, in Australia comprehensive educational campaigns include TV education, which describes symptoms associated with lower back pain and course of symptoms. This is designed to educate patients about the contexts in which their pain warrants a doctor’s visit. Many hospitals also have implemented “patient navigation programs.” These programs were developed to improve clinical outcomes for lower income Black women with cancer. Navigators work to address finance, insurance, coordinate appointments, address language and health literacy, and train patients to advocate for themselves.

References

Becker WC, Starrels JL, Heo M, Li X, Weiner MG, Turner BJ. Racial differences in primary care opioid risk reduction strategies. Annals of Family Medicine. 2011;9:219-25.

Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Fiellin DA. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: Psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:38-47.

Drwecki BB, Moore CF, Ward SE, Prkachin KM. Reducing racial disparities in pain treatment: The role of empathy and perspective-taking. Pain. 2011;152:1001-6.

Kaseweter KA, Drwecki BB, Prkachin KM. Racial differences in pain treatment and empathy in a Canadian sample. Pain Research & Management. 2012;17:381-4.

Staton LJ, et al. When race matters: disagreement in pain perception between patients and their physicians in primary care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(5):532-8.

Seamone, E. R. (2006). Understanding the person beneath the robe: Practical methods for neutralizing harmful judicial biases. Willamette Law Review, 42, 1-76.

Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Racial/ethnic disparities in the assessment and treatment of pain: psychosocial perspectives. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):131-41.