Let's talk about...

Empathy decline

Empathy of health care practitioners is an important aspect of the patient-provider therapeutic relationship. Mercer and Reynolds define empathy by three main components, including:

(1) an understanding of the patient’s situation, perspective and feelings;

(2) an ability to communicate this understanding and verify the accuracy; and

(3) create an action plan based on this understanding with the patient in a therapeutic manner.

Empathetic communication in healthcare has numerous benefits. Previously, empathy has been linked to increased symptom reporting by patients (Beckman and Frankel, 2003; Squier, 1990), improved diagnostic accuracy (Halpern, 2001; Larson and Yao; 2005), increased patient participation (Price, Mercer, and MacPherson, 2006), increased treatment plan compliance (Roter et al., 1997; Levinson, Gorawa-Bhat, and Lamb, 2000), and improved quality of life (Neumann et al., 2007).

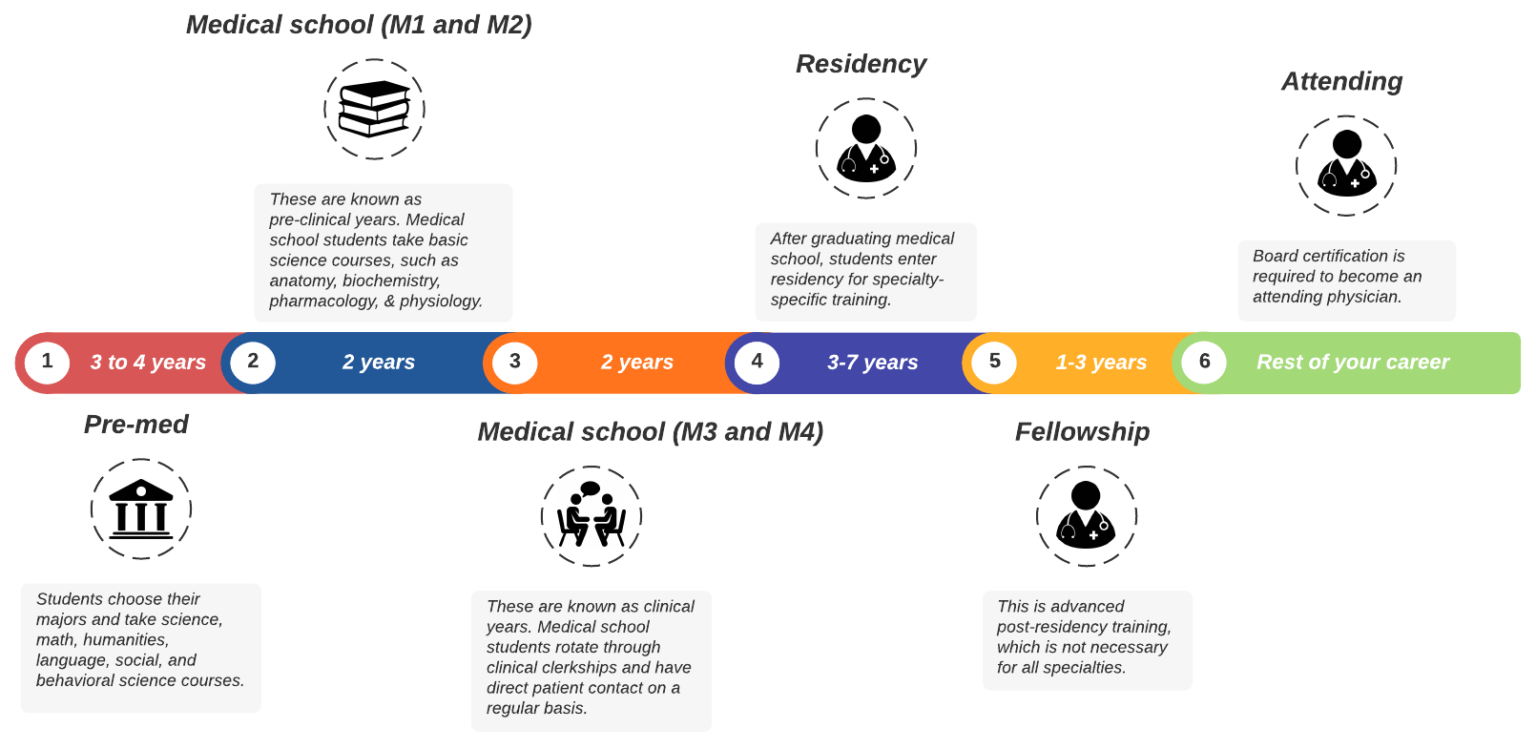

Interestingly, despite the benefits of empathy in health care interactions, a decline in empathy has been commonly reported during medical school and residency. Neumann and colleagues conducted a systematic review which examined 18 studies: 11 looked at empathy among medical students and 7 among residents. Both longitudinal and cross-sectional research demonstrated significant decrease in empathy during medical school and residency. Empathy decline happens most during the third year of medical school, which is a time when many students are having their first patient encounters. This suggests the empathy decline is related to some aspect of clinical practice. For example, students need to face realities of clinical practice and second hand human suffering can cause a shift in focus from the humanistic to more objective aspects of medicine.

See the image below for the key time points in medical training.

What factors are related to empathy decline?

(1) Specialty choice: highly patient-oriented specialties (e.g. family medicine) tend to be associated with higher empathy than patient remote specialties (e.g. radiology)

(2) First clinical encounter with a patient in medical school

(3) Distress of medical students and residents (e.g. depression, burnout, low quality of life)

(4) Negative aspects of the hidden curriculum (e.g. discrimination, belittlement, low social support)

(5) Negative aspects of the formal or informal curriculum (e.g. short length of stay with patients, incongruence between idealized view of medical professional by the media and inadequate role models in person; Neumann and colleagues, 2011).

Researchers are exploring a variety of interventions, such as mindfulness, self-awareness training, and reflective discussions about healthcare experiences. One can also target aspects of the “hidden curriculum” to promote better work environments.

References

Beckman HB, Frankel RM. Training practitioners to communicate effectively in cancer care: It is the relationship that counts. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:85-89.

Halpern J. From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medical Practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Larson EB, Yao Y. Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 2005;293:1100-1106.

Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(suppl):S9-S13

Neumann M, et al. Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: A structural equation modelling approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69:63-75.

Neumann M, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86:996-1009.

Price S, Mercer SW, MacPherson H. Practitioner empathy, patient enablement and health outcomes: A prospective study of acupuncture patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:239-245

Squier RW. A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationships. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:325-32Wh