Let's talk about...

Language in healthcare

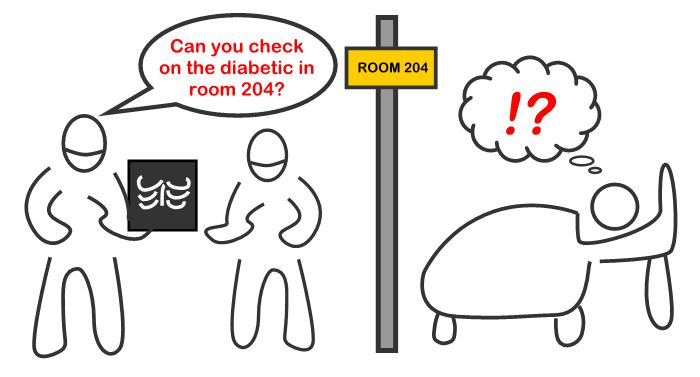

Historically, healthcare practitioners have been primarily taught in the biomedical perspective, which is an approach towards treatment and diagnosis that focuses on biological factors and excludes psychological and social influences. However, with biomedical perspectives it is important to be cognizant of the fact that we commonly speak in the biomedical perspective as well. By this I mean we hear the disease first and the patient second. When patients hear themselves associated with a disease first, it can lead them to over-identify with their illness, a term known as illness self-concept.

Illness self-concept is especially relevant to patients with chronic illness, as many of the negative aspects of the chronic illness experience are psychosocial. This means the greater a patient identifies with a chronic illness, the more problems there are with the person’s self-efficacy, adjustment, hopelessness, and treatment (Luyckz et al., 2016; Abraído-Lanza and Revenson, 2006). Therefore, in an effort to maintain patient dignity, it is important the humanity of the patient is incorporated of terms used in their presence. This means being cautious of referring to patients by only their disease or disability.

For example, the word “noncompliant” has been shown to leave patients feeling as if they lacked control over their health decisions. Reducing the use of labels like “non-compliant” or “diabetic” in the presence of patients is a common suggestion to increase patient satisfaction (Dickinson, 2018)

Dickinson conducted an interview-based study, which identified categories of terms that left participants feeling misunderstood and belittled. A total of 68 participants in focus groups were asked several questions to determine what terminology patients living with diabetes felt had negative connotations in the health care setting (Dickinson, 2018). Dickinson identified six categories of negative words/phrases in diabetes health care:

(1) Words associated with feelings of judgment, such as “noncompliant/compliant” and “uncontrolled/controlled.”

(2) Words leading the patient to experience anxiety or fear, such as “complications.”

(3) Words that serve as labels or make assumptions about patients, such as “diabetic” and “insulin-dependent.”

(4) Phrases that oversimplify and minimize their conditions, such as “you’ll get used to it” or “at least it’s not…”

(5) Phrases that indicate misinformation.

(6) Patronizing or accusatory language/tone.

Dickinson explored this topic in the context of diabetes-related health care, but it is important to note the same principles can apply to a variety of conditions.

What alternative terms can we use?

Some alternative to saying “the diabetic”, which focus on the person are: “the person with diabetes” or “the child who has diabetes” or “the adult living with diabetes.” For more suggestions about language in diabetes health care, see: Dickinson et al. (2017).

References

Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Revenson, T. A. (2006) Illness intrusion and psychological adjustment to rheumatic diseases: A social identity framework. Arthritis and Rheumatism 55 (2) pp. 224–232.

Dickinson, J. K. (2018). The Experience of Diabetes-Related Language in Diabetes Care. Diabetes Spectr. 31 (1), pp. 58-64.

Dickinson, J. K. et al. (2017). The Use of Language in Diabetes Care and Education. Diabetes Care. 40 (12), pp. 1790-9.

Luyckx, K. et al. (2016) Self-esteem and Illness Self-Concept in Emerging Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: Long-term Associations With Problem Areas in Diabetes. J Health Psychol. 21 (4) pp. 540-9.